News | June 9, 2011

Probes Suggest Magnet Bubbles At Solar System Edge

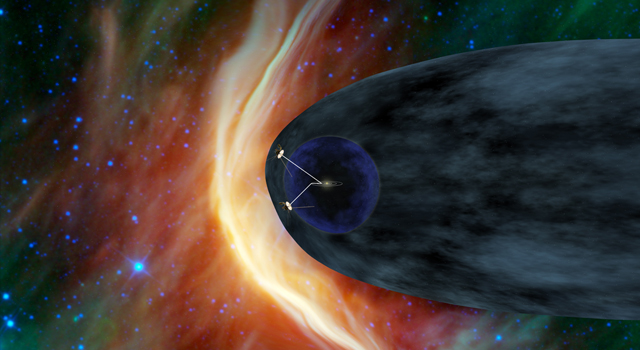

PASADENA, Calif. -- Observations from NASA's Voyager spacecraft, humanity's farthest deep space sentinels, suggest the edge of our solar system may not be smooth, but filled with a turbulent sea of magnetic bubbles.

While using a new computer model to analyze Voyager data, scientists found the sun's distant magnetic field is made up of bubbles approximately 100 million miles (160 million kilometers) wide. The bubbles are created when magnetic field lines reorganize. The new model suggests the field lines are broken up into self-contained structures disconnected from the solar magnetic field. The findings are described in the June 9 edition of the Astrophysical Journal.

Like Earth, our sun has a magnetic field with a north pole and a south pole. The field lines are stretched outward by the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the star that interacts with material expelled from others in our corner of the Milky Way galaxy. The Voyager spacecraft, more than 9 billion miles (14 billion kilometers) away from Earth, are traveling in a boundary region. In that area, the solar wind and magnetic field are affected by material expelled from other stars in our corner of the Milky Way galaxy.

"The sun's magnetic field extends all the way to the edge of the solar system," said astronomer Merav Opher of Boston University. "Because the sun spins, its magnetic field becomes twisted and wrinkled, a bit like a ballerina's skirt. Far, far away from the sun, where the Voyagers are, the folds of the skirt bunch up."

Understanding the structure of the sun's magnetic field will allow scientists to explain how galactic cosmic rays enter our solar system and help define how the star interacts with the rest of the galaxy.

So far, much of the evidence for the existence of the bubbles originates from an instrument aboard the spacecraft that measures energetic particles. Investigators are studying more information and hoping to find signatures of the bubbles in the Voyager magnetic field data.

"We are still trying to wrap our minds around the implications of the findings," said University of Maryland physicist Jim Drake, one of Opher's colleagues.

Launched in 1977, the Voyager twin spacecraft have been on a 33-year journey. They are en route to reach the edge of interstellar space. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., built the spacecraft and continues to operate them. The Voyager missions are a part of the Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

To view supporting images about the research, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/sunearth.

Written by: Jia-Rui Cook and Dwayne C. Brown

NEWS RELEASE: 2011-176