News | December 18, 2000

Most Distant Spacecraft May Reach Shock Zone Soon

A NASA spacecraft headed out of the solar system at a speed that would streak from New York to Los Angeles in less than four minutes could reach the first main feature of the boundary between our solar system and interstellar space within three years.

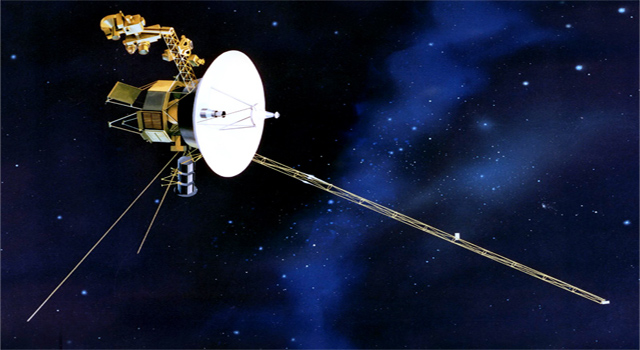

The Voyager 1 spacecraft, the farthest human-made object from Earth, may reach the beginning of his boundary region between early next year and the end of 2003, said Dr. Edward Stone, Voyager project scientist and director of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

The feature, called the termination shock, is not quite where the Sun's influence ends. It is where a pressure wave backs up from an even farther-out boundary, the heliopause, where the region of space dominated by particles streaming from the Sun ends and interstellar space begins.

But the termination shock won't stand still. Expected solar activity will likely crank up the solar wind of outbound particles and begin pushing back the heliopause in about three years, Stone said. The shock region could move outward even faster than Voyager 1.

"If we don't encounter it in the next three years, we may not catch up with it for several more years," Stone said. "On the other hand, it would be wonderful if we got out past it, then it overtook us so we could have a second look at it."

Stone estimated the distance to the shock and the heliopause during a Monday session of a five-day conference of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Voyager 1, built, flown and managed by JPL, left Earth in 1977 and made a string of discoveries while flying past Jupiter in 1979 and Saturn in 1980. It is now about twice as far from the Sun as Pluto's orbit. Its twin, Voyager 2, made a grand tour of four outer planets and is currently about 80 percent as distant as Voyager 1. NASA's current mission for both craft is to learn more about the edge of the solar system and what is just outside of it.

As the Sun moves through the galaxy, it hauls with it a surrounding bubble, the heliosphere, filled with particles of the solar wind. The solar wind carries an average of only about a half-dozen ions per cubic centimeter (about 100 per cubic inch) at Earth's orbit and even fewer farther from the Sun, but it exerts an outward pressure and extends the magnetic influence of the Sun.

Somewhere roughly 100 or more times farther from the Sun than Earth is, the pressure of the solar wind is counterbalanced by a pressure outside of the heliosphere. That's the pressure of the interstellar wind, a faint current of particles flowing through the galaxy. The interstellar wind surrounds each star's sphere of influence like a river around rocks whose shapes could change like elastic balloons.

"We're hoping to learn how big a bubble the Sun creates for itself and, for the first time, how much pressure there is in interstellar space," Stone said.

One method of estimating the distance to the bubble's edge makes use of radio emissions that are believed to originate from the boundary between interstellar space and the heliosphere in response to bursts of particle ejections by the Sun. Measuring the time lag between when a solar burst occurs and when the response echoes back to the spacecraft allows a calculation of how far the particles traveled to reach the heliopause.

Another method uses the difference between the rate at which cosmic rays of a certain type are reaching Voyager 1 and the rate at which they are reaching Voyager 2.

Those methods and others suggest the termination shock may be 80 to 90 times as far from the Sun as Earth is, Stone said. That's farther than anticipated earlier in the Voyager mission.

The shock is expected to have particle-density and magnetic- field characteristics that will make its detection unambiguous when Voyager 1 reaches it, providing an accuracy check for the ideas used in predicting its location.

"Once we know where the termination shock is, we'll have a better idea how much farther it is to the heliopause," Stone said.

Additional information about the Voyager Interstellar Mission is available at http://vraptor.jpl.nasa.gov. JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C.

Written by: Guy Webster (Jet Propulsion Laboratory)