News | July 8, 2004

Blast Wave Blows Through the Solar System

Had Shakespeare been a solar physicist, he may have written, 'hell hath no fury like the Sun'. Although the Sun provides the means for life on Earth, it has a dark side - the Sun regularly sends massive solar explosions of radiative plasma with the intensity of a billion megaton bombs hurtling through the solar system. Perhaps even more astounding, scientists now have the ability to track that energy billions of miles away thanks to an armada of explorers including Mars Odyssey, Ulysses, Cassini and the Voyagers, not to mention solar and Earth-orbiting craft.

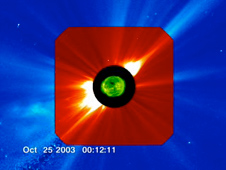

It was with this unprecedented scientific fleet that scientists observed the events that took place in late October and November when the Sun unleashed the most powerful solar flares ever detected. A sort of timeline emerged tracking the largest of the related coronal mass ejections (CMEs) from the Sun all the way to Voyager 1 (expected to receive the shock blast sometime this month), then on to the heliopause which delineates our solar system from interstellar space. The force of the blast is expected to extend that region by as much as 400 million miles.

All told, about 17 major flares erupted on the Sun during those two weeks, the result of energy building up in the Sun's magnetic field lines until they become strained enough to suddenly snap like an overstretched rubber band. The related coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are the largest explosions in the solar system, capable of launching up to 10 billion tons of electrified gas into space, normally at speeds of one to two million miles an hour. While we're protected by Earth's magnetosphere and atmosphere, power grids, radio and GPS signals, satellites, and astronauts in space are vulnerable.

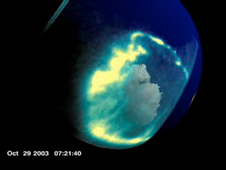

Fortunately effects on Earth from these events were minimal, in effect a testament to the fleet of monitors that issued warnings as early as Oct. 21. Most Earth-orbiting spacecraft were put into "safe mode" to protect them from the massive onslaught of radiation. Power grids were safe with the exception of a blackout in Sweden, airplanes were rerouted to more southern routes to move them away from the increased radiation at the pole, and auroras were spotted as far south as Florida. At Mars, the MARIE instrument on the Mars Odyssey spacecraft was not as lucky. Ironically its task was to better understand solar radiation on Mars. It was able to make observations up until a powerful Oct. 28 CME overheated a power converter.

When Ulysses was launched in 1990, it used the gravitational fields of Jupiter to get into its unique orbit to study the heliosphere surrounding our solar system. Between November 2003 and April 2004, it was again aligned with the planet, giving scientists a good idea of the effects in the vicinity of Jupiter. Cassini, now busy exploring Saturn's rings and moons, caught the blast on Nov. 11. Among its dozen instruments is the Radio and Plasma Wave Science (RPWS) instrument, which measures the electric and magnetic wave fields in space and within planet's magnetic fields. It detected solar radio bursts from the particularly intense flares. By downshifting the frequencies and condensing the data from four hours to 15 seconds, researchers were actually able to make a sort of 'soundbite' of Cassini's data.

To fully appreciate this long-distance tracking marvel, the 26 year-old Voyagers 1 and 2 are located about 7 and 9 billion miles from Earth, respectively. That places them about four billion miles past Pluto's orbit and headed toward the outer reaches of our solar system. The amazing part: scientists still hear from Voyagers on a daily basis. They send back about 12 hour's worth of data per day at about the speed of a slow modem and with the power of a 28-watt nightlight. Literally journeying out farther than any man or spacecraft has been before, these two are charting new territory and rewriting science books regarding the view from out there. Scientists have a lot of theories as to what happens to the boundary of our solar system with relation to solar activity; nearly nine months after the Sun spat out this enormous blast, Voyager 1 is going to tell us just what happens.

For future astronauts who travel to other planets, having a better understanding of solar events is crucial. Today careful monitoring makes sure that those on the International Space Station stay out of harm's way by warning them before big blasts so they can take cover in a more heavily shielded section of the station. They also have the benefit of some of Earth's magnetosphere as protection, something Mars-bound astronauts won't. Possible health risks from the energetic solar plasma include cancer, acute radiation sickness, hereditary effects, and damage to the central nervous system. And because different planets have different magnetic and atmospheric shielding and experience different effects from the solar wind on a daily basis, having detectors spread throughout the solar system is helping us to better understand our surroundings and make future plans. After all, who goes on a big trip without first checking the weather reports?

Written by Rachel A. Weintraub, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center