News | October 2, 1989

Voyager 2 Discovers Eruption on Triton

Five-mile-tall, geyser-like plume of dark material has been discovered erupting from the surface of Neptune's moon Triton in one of the images returned last month to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft.

The discovery comes just as the Neptune encounter -- Voyager 2's fourth and final planetary flyby in 12 years -- officially ends today (Oct. 2).

This is the first time geyser-like phenomena have been seen on any solar system object (other than Earth) since Voyager discovered eight active geysers shooting sulfur above the surface of Jupiter's moon, Io. The new finding -- Voyager's last hurrah in its journey past the planets -- augments Triton's emerging reputation as the most perplexing of all the dozens of moons Voyager 1 and 2 have explored.

Voyager's camera captured the eruption shooting dark particles high into Triton's thin atmosphere on August 24 from distance of 99,920 kilometers (about 62,000 miles).

Resembling smokestack, the narrow stem of the dark plume, measured using stereo images, rises vertically nearly eight kilometers (five miles), forming cloud that drifts 150 kilometers (90 miles) westward in Triton's winds.

The feature was recognized by examining several images taken from different angles and analyzed through stereoscopic techniques.

While Voyager scientists are still trying to determine the mechanism responsible for the eruption, one possibility being considered is that pressurized gas, probably nitrogen, rises from beneath the surface and carries aloft dark particles and possibly ice crystals. Whatever the cause, the plume takes the particles to an altitude where they are left suspended to form cloud that drifts westward.

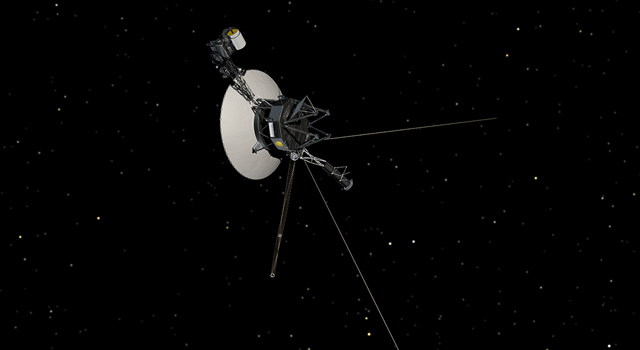

Voyager 2's working life among the planets may be at an end, but the spacecraft and its twin, Voyager 1, are expected to continue returning information about the various fields and particles they encounter while approaching, and eventually crossing, the boundary of our solar system. The plutonium-based generators that provide electricity to the spacecraft are expected to keep alive the computers, science instruments and radio transmitter for up to 25 or 30 more years.

As of today, the long-lived project will be known as the Voyager Interstellar Mission.

The Voyager Project is managed for NASA's Office of Space Science by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.